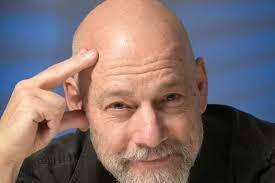

Darío Volonté, tenor and Malvinas veteran: “In addition to malvinizing Malvinas, we have to transform ourselves into a powerful country”

Before turning to music and traveling the world singing, Darío Volonté served in the Argentine Navy, serving as a naval machinist aboard the cruiser ARA General Belgrano during the South Atlantic Conflict. War, music and resilience in this dialogue about life.

In his adolescence, Darío Volonté entered a fishmonger accompanied by his mother and found a poster from the Argentine Navy that invited young people to join the Force. He did not hesitate, not because of his vocation, but because he considered that it was an opportunity to work and train at the same time. He became a naval machinist and, in 1982, he was assigned to the cruiser ARA General Belgrano, sunk during the Malvinas War. He survived, came back and went out in search of new opportunities.

While working as a freighter, he joined the Church choir. His voice reached the ears of baritone José Crea, a World War II veteran, who trusted his potential and agreed to collaborate in his artistic training. He clung to that new opportunity that life gave him and managed to sing Tosca at the Opera theater. Since then, he has appeared on many of the most important stages in the world. In Argentina, for example, he became the only artist in the history of Columbus to have performed two encores.

Thirty hours in a freezer

-How did you end up on the General Belgrano cruise ship?

-I was not from Belgrano, I was originally on the frigate Libertad, but I went to the cruise as a reinforcement. At that time, I was a machinist and they said that the personnel they were going to detail had to take the naval bag, their belongings and go to Belgrano to participate in the South Atlantic Conflict. They appointed me, so I put together what little I had. Precisely, the spirit of the sailor is to have everything prepared, for anything. I grabbed my bag and we went on a bus to Constitución station. From there, by train to Bahía Blanca and then we took a bus to Punta Alta. From there, to the Belgrano boiler, with a shift from 4 to 8 and another from 16 to 20. That was my combat position: putting in and taking out burners, pressure, fuel filter, heaters... It was my world until the moment of the sinking.

-How did you experience sailing to the Islands?

-First we went to Ushuaia, where we resupplied and spent the night. Then, we passed through the Island of the States to later go to the conflict zone. During the navigation, abandon ship drills and other combat drills were carried out, in which all positions had to be reinforced, such as artillery, machinery, breakdown control, electricity, or the command bridge. I mean, there was a lot of training, we knew how to use all the survival elements. Years later, I learned that, among all naval tragedies, the Belgrano was one of the sinkings with the highest percentage of survivors. We were 1,093 troops and 323 deaths were recorded.

-Do you remember what happened when they were attacked?

-We were lucky to escape the torpedo, because it was by engines and I was in the boilers, very close. Almost all of the machine workers died. I remember that when we were already on the rafts there was a huge storm. The closest thing I saw to the movie A Perfect Storm. What you see in the film is what I keep in my memory, for example, the size of the waves. Until that moment, I was unaware that there was a thermal sensation of -20 ºC. Over time I was able to relate it: the freezer in one's house is at -14 ºC. So, it was like being inside a freezer, humid and beaten into a rubber raft for 30 hours. In the middle, the rafts turned around. With the storm we ended up 140 km south, towards Antarctica.

-Did your raft turn over?

-Yes. A wave covered us and we were down for a few seconds. The typical scene where life goes through your head. From your childhood until that day. Everything happened to me: my life as a boy, high school, my old woman... When I thought about my old woman, I said to myself: "Poor woman." She was widowed, 28 years old, with two children, my brother and me. At that moment I thought that if he lost his eldest son, it would be a disgrace. It was just when the raft turned over. After a while it began to deflate. We look for the inflator and the spout. Water also began to enter. On top of that, there were more of us than we should have: it was a raft for 15 and we were 23. But, that misfortune ended up being a blessing because, being heavier and well inflated, it was more difficult for it to turn over again.

"After the war, what remained with me is that there are no small or big things. It is all the same. In the small is the genesis of everything. That is why God is in everything" (Fernando Calzada)

Living after the war

-Did being in the War change you?

-We can use the "thank God" for everything or nothing, that can change the meaning of life and, in addition, modifies the type of search towards the spiritual. After the war, what remained with me is that there are no small or big things: this report, having a mate at night while studying something, singing at the Colón, or simply fooling around. It's all the same. The issue of size is an illusion, that is why it is said that the flame of a weed burns the universe. The genesis of everything is in the small. Therefore, God is in everything. That's what I believe. Even thinking that this life is the only one that exists is limiting.

-¿How do you experience the Malvinas cause?

-At first I focused on working and moving forward. Later, when it began to remalvinize, I became more aware. When you step away from a big plot, you can see everything from another perspective. If it can be done spiritually, much better. And, if there is no ego, even more so. It's all an energy issue.

Regarding the Malvinas cause, until we are well, it is lost. If we don't get our act together by developing ourselves economically, socially and mentally, there is no way out. It is no coincidence that the British returned Hong Kong to China when it became a power. If you visit the Malvinas Museum, where the ESMA was, you can see that there were YPF tanks or LADE flights on the Islands. But we were another economy; I lived in that country

.-What Argentina do you remember?

-My mother was widowed at the age of 28, we lived in a rented apartment in the Federal Capital. We would go on vacation and go to eat pizza and go to the movies every weekend. Today, to make that life, you have to earn a lot of money. At that time, she earned it by working in a factory. In fact, when my father died, she had four or five pieces of paper with addresses to choose the job she wanted. Unemployment did not exist. I lived in that country. In the Falklands, Argentina saw itself differently. There were flights and exchanges. That is why I say that we were one step away from living with shared sovereignty or with that which corresponds to us.

Afterwards, war was involved, the Islands began to move away. I believe that, in addition to malvinizing, we have to transform ourselves into a powerful, powerful and strong country. We were and, in a way, we are. We have everything, we have to order it. It "s like everything in life

-Do you value your country?

-Logical. I love my country. For me it is the expansion of my house or my neighborhood. Each place is an extension of my own individuality. And I defended that. For this reason, the Homeland hurts us more as war veterans, because we were in a war, we went through crises, we saw poor children, a destroyed economy and we learned nothing. Every kid who dies or suffers from malnutrition is an Argentine who is at war. It is painful and unfair. Therefore, for me the great issue of the Homeland is mostly spiritual. Until we fix this, the Falklands will be thousands of kilometers away. First we have to heal our wounds, agree and move forward. Then everything comes by itself.

"My goal was to make a living from music, and it happened. Then, singing at the opera in Rome or at the Colón, it happened. Contracts began to arrive when I sang with an artistic level and with excellence. Doors are opening and destiny It takes you where your soul wants" (DEF File)

A musical childhood

-Considering that your mother was widowed very young, what was your childhood like?

-The memories of this stage are good. I grew up in another Argentina, with another idiosyncrasy. It was a freer, more open childhood with different types of habits. I feel that I had a childhood, on the one hand, very sacrificed and, on the other, always very optimistic. My mother could have influenced that, who was always very cheerful, despite the blows she had to endure in her life. For example, there was always music at home. Saturdays were the days she bought records. That's how I met Camilo Sesto, the trio Los Panchos or Gardel, all artists with very beautiful vocals. That repertoire influenced a lot and led me to mix the lyrical with the popular.

-What was your mother's role in your life?

-She came from a very quiet, country background. My whole family is from Entre Ríos and the people from Entre Ríos are very simple, frontal and optimistic. She was always at the level of the demands of the time: it was work or study. I decided to study. Then, I went out to work. Later, I went to study in the Navy, which was a mix of study, work and military service. I remember, for example, that we had to do the famous preliminary selection period: almost 10,000 applicants entered and only 2,500 had to remain. In those days I lost 17 kg. I was 15 years old and had entered at 1.73 m tall (later I reached 1.81 m, which is what I am now). When it was my turn to return home, I tied my pants with a piece of cable, because I had shrunk. When she saw me she almost started crying.

My mother was a very simple and open woman. He only had the 4th grade of school and, however, he always cared about reading and learning. He sought to develop reading and intellect in us, so that we could be independent and have freedom in life. When I dedicated myself to singing, which was perhaps a higher-ranking job, for her it continued to be a job.

-How did all that impact you?

-When you remember, try not to lose some moments. On Sunday mornings, at home, my mother made mate and we drank mate cooked with milk and toast with butter and a little sugar. That was supreme happiness. Again, everything is important: this interview, a night at the Colón, a concert at Luna Park, eating a piece of barbecue with a split tomato or having a mate under a tree. Everything has enormous vital importance, because everything is present, it is life and energy. It is what we have to be able to continue projecting the future. My mother, in that sense, with her basic, day-by-day survival thing, also had enormous resilience, because she had a very sacrificial life. But, he raised us with optimism and I try to raise my family the same way.

Vivir de la música

-You married Vera Cirkovic, also an artist…

-Yes. Plus, I have two daughters. My family nucleus was always a simple way of thinking about life. I try to capitalize on everything. Because my old man died when I was very young and, along the way, patrons appeared who trusted me and my talent, they even paid for my first ticket to Europe and supported my family at that time.

I always mention Carlos Humeroti and Guigui Gallardo. There is also José Crea, a World War II veteran, a singer from Colón, who taught me singing and never charged me a cent. Later I met Alfredo Estrafada, in Europe, who was my first agent and artistic representative. Obviously, when I lost my biological father, others appeared to fill that role. You have to try to get the most positive out of every situation.

"I try to touch the sky with my hands at all times. Maybe, for me, it means having freedom" (Fernando Calzada)

-How do you remember your dad?

-My father died young and was an optimistic person. He had a voice ten times louder than mine. I remember that, when I got home, it was a loud voice that came in. He was a much bigger man than me. All those images stayed with me. And, all the guys who appeared with father roles had characteristics of him.

-You went through several artistic instances, did you ever feel like you were touching the sky with your hands?

-I didn't have it, I didn't think things through. Within my freedom, I try not to set a goal for myself. My goal was to make a living from music, and it happened. Then, singing at the opera in Rome or at the Colón began to happen. The contracts were arriving by singing with artistic level and with excellence. Doors are opening and destiny is taking you where your soul wants.

There were, perhaps, three or four moments in which I said: "How nice this is happening," but since my goals were so small and everyday, it was more about managing to climb step by step. In fact, I try to touch the sky with my hands at all times. Maybe, for me, it means having freedom.

By Patricia Fernández Mainardi - Font: DEF