2023 in the Sahel: a geopolitical change marked by distancing from France

The year 2023 witnessed a continuation of the transformations and geopolitical evolution in the African region of the Sahel, which already began a few years ago. Following coups in Mali and Burkina Faso, Mohamed Bazoum, president of Niger, elected in 2021, was overthrown by a coup on July 26. This series of regime changes has forced France, now rejected in what it considered its zone of influence, to question its military and diplomatic presence in the region.

This year, news in the African region of the Sahel has been marked by similar scenes: in several countries in the area, thousands of civilians have carried out important and recurring demonstrations, denouncing what they consider France's neocolonialism and demanding the withdrawal of the troops of the European nation stationed in its territories.

Sahel countries, including Mali, Burkina Faso and Niger, have noted that since their independence in the 1960s they have been considered France's "backyard" in Africa.

But today, the former colonial power is no longer welcome there. In this part of the African continent, located between the Sahara and sub-Saharan Africa, France appears more destabilized than ever between the memory of its lost influence and power and its lack of understanding towards evolving African societies, now influenced by new convictions and political actors. and religious.

The Sahel: instability tests the Armies

To understand the current situation in the Sahel, it is necessary to go back a decade, when at the request of the Bamako authorities, France launched military operation Serval.

The situation in Mali was becoming increasingly frightening for the central government, which feared a fragmentation of the country. For months - after the fall of Muammar al Gaddafi's regime in Libya in 2011, which released a flow of weapons and destabilized the region - Mali was on the verge of collapse.

The entire north was occupied by jihadist groups, as well as Tuareg, with divergent objectives and motivations, but their temporary alliance threatened to collapse the country.

After France's intervention, a kind of illusion of return to normality occurred. The main cities in the north, under the control of armed groups, were retaken within weeks and the militias were dispersed into the Malian desert after suffering significant losses.

But the relief was short-lived. The Armed Forces did not manage to completely and definitively annihilate the combatant Islamist organizations, which managed to reconstitute themselves after several months.

To prevent its return, Paris decided in August 2014 to transform Operation Serval into Barkhane and expand its military intervention to all the G5 Sahel countries, which in addition to Mali included Burkina Faso, Mauritania, Niger and Chad. However, according to specialists, although Operation Serval was a partial success, Barkhane did not suffer the same fate, despite what the French Army claims.

Paris lists its successes: in nine years of intervention in the Sahel, its special forces have managed to eliminate several jihadist leaders and senior commanders of groups such as the katiba Tarik Ibn Ziyad, Ansar Eddine, Al-Mourabitoune, the Oneness Movement and the Jihad in West Africa (Mujao), Al Qaeda in the Islamic Maghreb and the self-proclaimed Islamic State in the Great Sahara, among others.

This year, President Emmanuel Macron even stated that "if France had not intervened, if our soldiers had not fallen on the field of honor in Africa, if Serval and then Barkhane had not decided, today we would not be talking or of Mali, nor of Burkina Faso, nor of Niger. These States would no longer exist today in their territorial integrity."

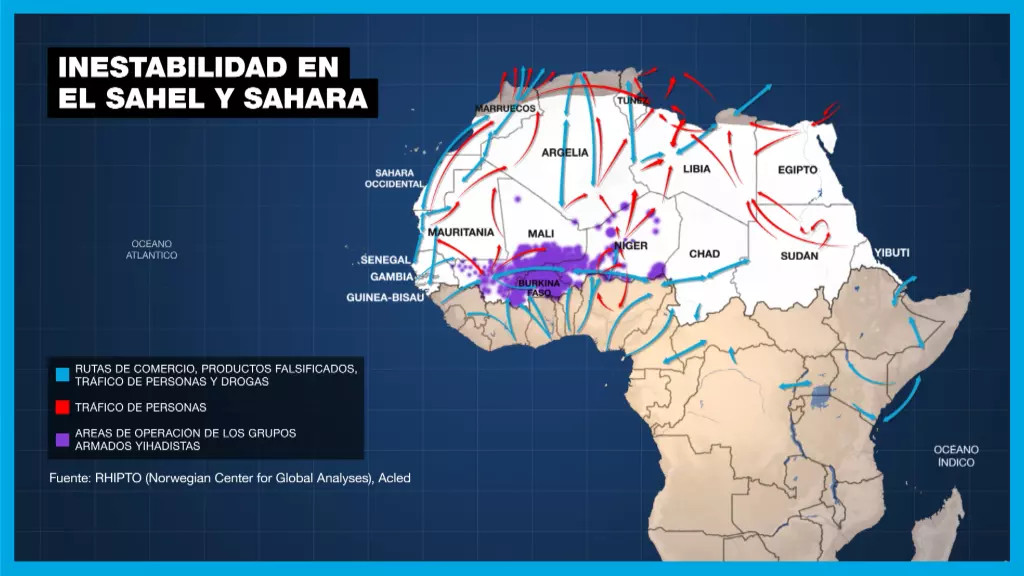

However, these statements are contradicted by the observations of experts who highlight another reality on the ground: in terms of sovereignty, Mali, Burkina Faso and, to a lesser extent, Niger, have seen large areas of their national territories escape their control. control, and the activity of non-state armed groups continues to expand, posing a threat to several southern countries, such as Côte d'Ivoire, Togo and Benin.

In November 2020, Morten Boas and Francesco Strazzari, professors of international relations, detailed in the pages of the political science magazine The International Spectator that "international forces and their national allies (...) cannot achieve a decisive military victory on the insurgents."

Specialists add that "the main jihadist leaders can be eliminated, but the trajectory of insurrections in the Sahel shows that, when one leader falls, others emerge."

Successive coups d'état and rejection of France

Faced with the failure of the Barkhane operation after years of military intervention and the advance of jihadist groups, public opinions in the Sahel have finally turned against the former colonial power, now blamed for the violence that mainly affects civilians.

For many inhabitants of the Sahel, it is incomprehensible that an Army with advanced resources has not managed, in so many years, to defeat combatants with archaic methods, who move around on motorcycles and are armed with automatic rifles.

Analysts explain that France has been involved in a double game: the country would have supported, and even armed, jihadist groups to capitalize on the chaos they cause and thus secure the natural resources of destabilized nations. In summary, some propose that neocolonial France would have fueled conflicts in the Sahel in order to plunder the wealth of these nations more effectively.

As a result of this panorama, since 2020, a succession of coups d'état led by the military who considered their governments ineffective and subordinate to France have hit the nations of the Sahel, including Mali, Burkina Faso and Niger.

The military junta that now runs these countries has managed to win the sympathy of the population, using convincing political arguments, such as the fight for national sovereignty and against "French neocolonialism", or remembering the consequences of past colonialism.

During the coup d'état in Niger last July, the junta that took power followed the example of the coup plotters in Mali and Burkina Faso by beginning a process of distancing itself from France.

Thus, after withdrawing its troops from Mali and Burkina Faso, Paris also withdraws its troops from Niger. In this context, other powers, including Russia, continue to expand their influence and are now perceived as preferable political, economic and security partners to the former colonizer.

However, pro-Russian sentiment is not new in the Sahel. During the era of decolonization, the then Soviet Union established close ties with several African territories and supported them in their struggle for independence. In the midst of the Cold War, Moscow trained numerous African leaders and elites.

In this way, Russia presents itself with a solid argument in Africa: it was never a colonial power and, on the contrary, it supported the independence movements in these countries.

This year, during the Russia-Africa summit in St. Petersburg, Moscow reaffirmed its desire for equal relations with Africa, and President Vladimir Putin praised a new "multipolar world order" without "neocolonialism."

For its part, China, an economic power present in the Sahel, has won African sympathy by adopting a strategy that has resonated strongly: promises of development aid and not interfering in internal affairs.

In this way, France's presence in the Sahel has weakened, leaving room for the rise of other powers. What began with Mali and Burkina Faso continued with Niger and raises questions about what could happen in countries such as Senegal, Ivory Coast and other nations in the region.

Font: France 24